Women in Indian Politics: Participation versus representation

- Home

- Uncategorized

- Women in Indian Politics: Participation versus representation

Over the years, the participation of women in Indian politics has increased significantly. However, it has yet to translate into a significant representation of women. While there have been pronouncements by the political parties of voluntary reservation for women in seats, nothing much has happened. The women’s reservation bill is still being debated and is unlikely to become law soon. The rationale for having more women representatives is that it facilitates the representation of specific interests of women in policies and programs.

The note details the participation and representation of women in Indian politics and why, despite increased participation, women’s representation in politics remains low.

While political participation and representation transcend electoral politics, for this note, it is restricted to electoral politics.

Participation and representation of women in politics

For this note, participation includes membership in political parties, campaigning for candidates, and voting during the elections. Representation is contesting the elections and being an elected representative.

There is no publicly available data on political party membership or the number of women campaigning in elections. However, a study by the Center for Study in Developing Societies indicated that women’s participation in election rallies, campaigns, door-to-door meetings, and distribution of pamphlets

increased between 1996 and 2019, more so between 2014 and 2019.

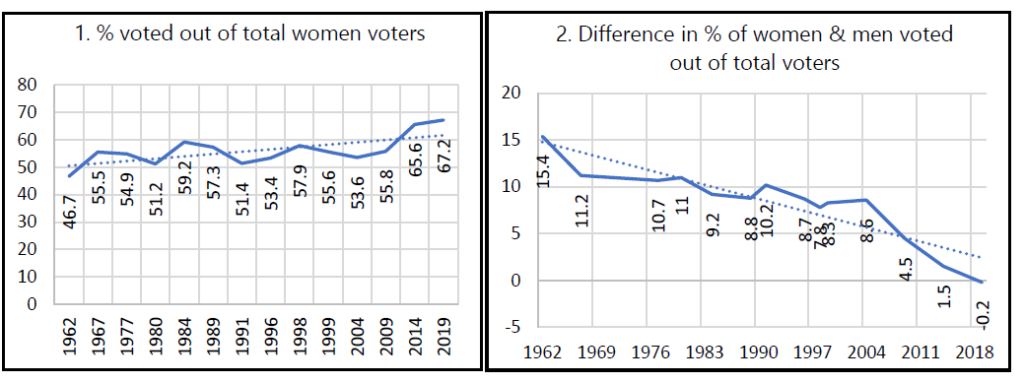

The data on women voters available in the public domain indicates that the proportion of women voters has increased significantly over the years. In 1962, only 47% of the women registered as voters voted in the election. In 2019, it increased to 67.2%. The increase has been steady (Graph 1)3

- The data for this note is mainly drawn from the Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation (MoSPI), Government of India (GOI). Women and Men in India, 2022. 24th issue.

- It is interesting to see the elections where there was a significant spike in the proportion of women out of the total women voters who voted- 1967 and 1984 (following the demise of major leaders – Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi) and 2014 (Prime Minister Modi contesting the first time in a parliamentary election).

The difference in the turnout of women and men in the elections was about 15% in 1962. In 2019, the proportion of registered women voters voting in the election was marginally higher than that of men (Graph 2). The trendline indicates that the difference between women and men registered voters voting in elections has steadily declined. This fact is often held up to indicate that the elections in India are gender-inclusive.

However, is the participation translated into the representation of women in politics?

Representation of Women in the Parliament

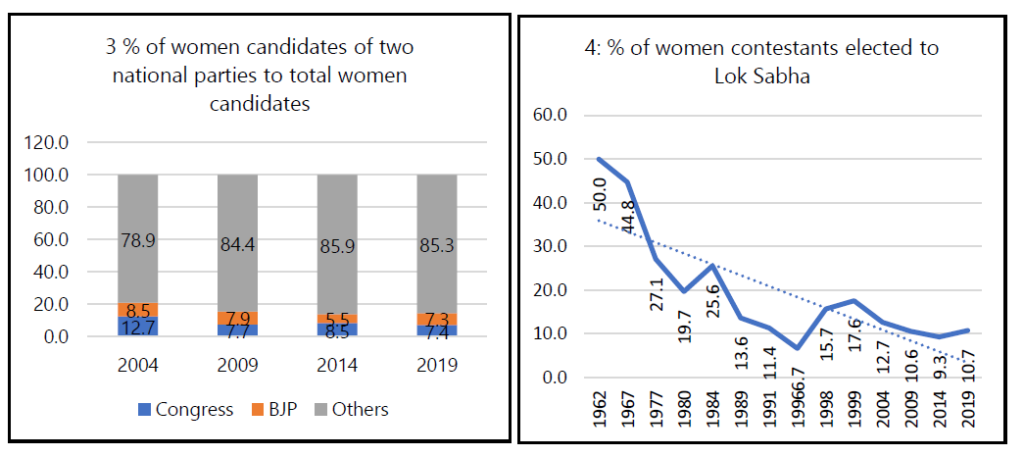

Between 1962 and 2019, the number of women contestants increased by ten times. However, the smaller and regional parties have contributed to this increase. The number of women candidates fielded by the two major national parties4 has mostly stayed the same between 2004 and 2019. In 2019, the number of female candidates accounted for only about 12% in both these parties (Graph 3).

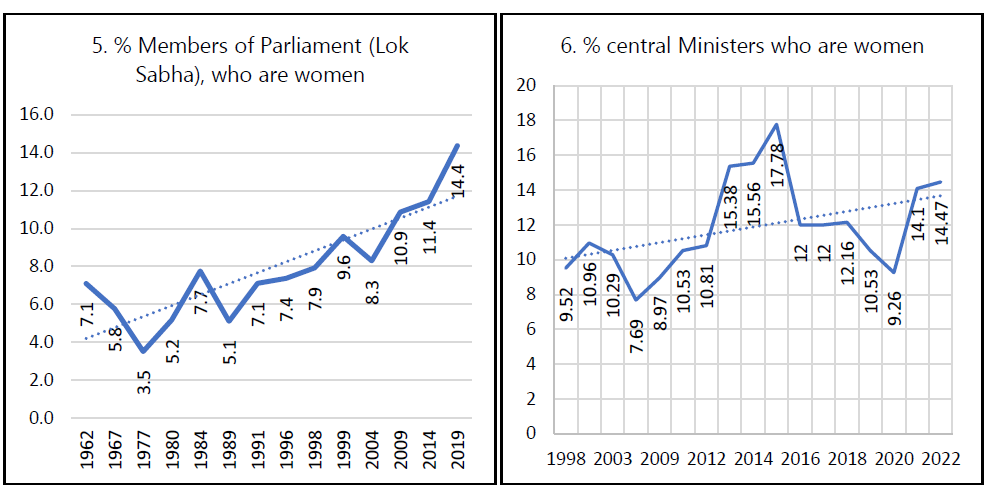

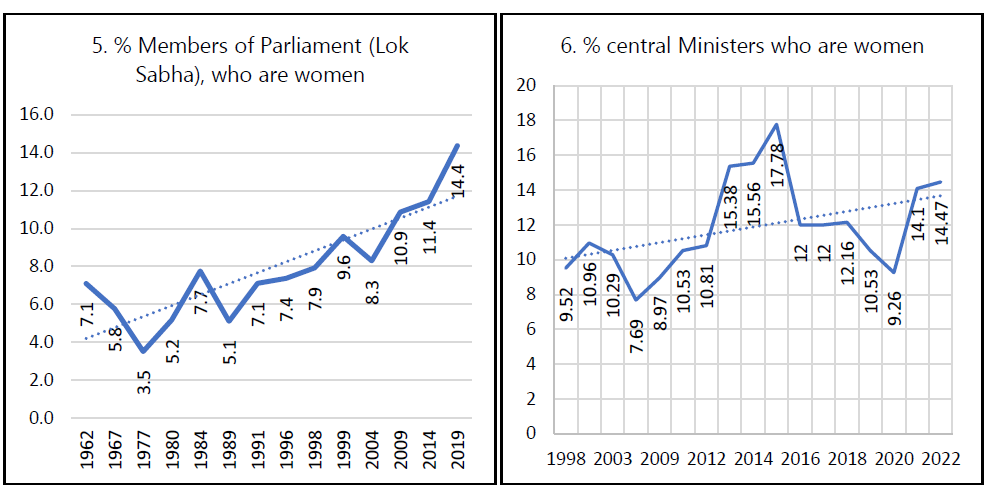

Over the years, the proportion of women contestants elected as Members of the Parliament (MPs) to the Lok Sabha has declined. Only about 10% of the women who contested for the MP post were elected in the last three parliamentary elections (Graph 4). The decline is partially also due to the increase in women contestants. As mentioned above, the number of women contestants increased ten times between 1962 and 2019. While there has been an increase in number, it has not resulted in a commensurate proportion of women getting elected to the Lok Sabha. The proportion of elected women MPs was always less than 10 percent between 1962 and 2009. It increased marginally in 2014, and only in 2019, close to 14% of elected Lok Sabha representatives were women (Graph 5). The representation of women in the Rajya Sabha, too, is not significant.

Women’s representation as ministers was also not significant. In 2016, women accounted for about 18% of all ministers in the central government. It was often less than 10% before that, and after 2016, too, it declined. Only in 2020 did the proportion of women ministers increase closer to 15% (Graph 6). Of the 11 women ministers in the Government of India, now, only two are cabinet ministers. The representation of women as Members of the Legislative Assemblies (MLAs) across states is also not very significant (Graph 7). Interestingly, some of the northern states have a higher proportion of women MLAs than the southern states!

Representation of women in the Panchayati Raj

Following the 73rd and 74th constitutional amendments and efforts of many states to reserve seats in Panchayati Raj Institutions, the representation of women has increased significantly. In many states, 50% or more of the PRI members are women.

While there are reports of proxy-Sarpanch, with men controlling the processes, the representation of women is very encouraging. The Indian government has managed to showcase women’s representation in local bodies to elevate its ranking in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap report.

Why are women’s participation and representation important?

Two contrasting aspects emerge from the above description. Women’s participation in electoral politics has been significant. However, their representation is significantly limited to the PRIs, where recent affirmative actions (reservation) have enabled their representation. On the contrary, their representation in the state legislature, national Parliament, and as ministers are very limited. Women have been unable to break the glass ceiling beyond the PRIs and be represented in the higher corridors of power. In some sense, there is a “gender exclusion” of women beyond the PRIs. Studies have indicated that many women who have managed to break the glass ceiling are often from political families.

Some of the reasons women cannot break this barrier include the nature of party leadership in many instances, which is controlled mainly by men and often for life. There are other structural barriers, too. The nature of electoral politics and the violence often associated with it also hinder women from contesting. Elections are expensive, and often, women do not have access to resources to fight the elections. Also, none of the political parties acknowledge women’s reproductive role as a social responsibility.

There must be a commensurate representation of women, given their electoral participation and, most importantly, their contribution to society and the economy. Their representation in the state assemblies and the Parliament is essential to bring in gender perspectives in political decision-making processes at higher levels and to ensure gender-friendly legislation. The evidence of women’s effectiveness as leaders and their positive association with development is now well established. Women elected under reservation in Panchayat institutions invest more in public goods. The women leaders’ investment often reflects community priorities, such as drinking water, child nutrition, and health centers. A study has also found that women legislators in India raise economic performance in their constituencies by about 1.8 percentage points per year more than male (legislators).

It would be ideal if the political parties voluntarily enabled increased participation and representation of women. This would help to counter the arguments that a reservation for women militates equality. However, as outlined above, political parties are often the gatekeepers for women’s electoral participation and representation. Hence, affirmative action by the State appears to be the way out as it will help to overcome the various structural challenges women face, as the experience with PRIs demonstrates.

The reservation will help the electorate to get an idea of women as leaders. It would also help to break the stereotype that only men could be leaders. It could also enable younger women and girls to consider the leaders as role models and consider politics an option.

While it is unlikely that there will be a significant change by the 2024 elections, by 2029, the reservation for women in the state and the national elections is necessary to ensure that more women represent us, enabling a more equitable and sustained development.