Bio-medical waste management in India Challenges and measures for better management

- Home

- Uncategorized

- Bio-medical waste management in India Challenges and measures for better management

India has a comprehensive guideline on Bio-Medical Waste (BMW) management, which has evolved over the years, culminating in the Bio-Medical Waste Rules 2016. There have been few amendments to the rules, specifically during the Covid. Despite the guidelines, BMW management still poses some challenges. There are specific challenges at two levels. One is the non-adherence to the guidelines in some states, and two is the institutional challenges.

What is Bio-Medical Waste?

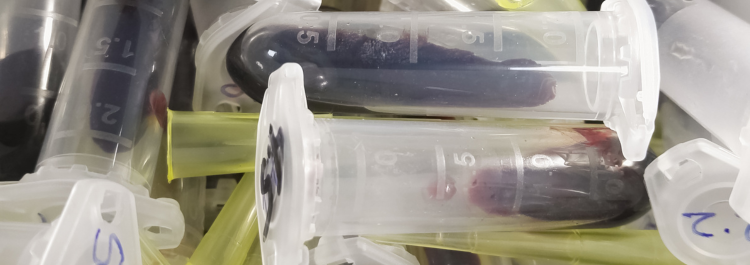

Hospitals, or HCFs, generate significant waste. As the WHO indicates, 75-90 percent of this waste is non-hazardous. A small proportion, referred to as BMW, is potentially hazardous. The BMW is generated in pharmacies, wards, operations theaters, and others (see https://cpcb.nic.in/uploads/Projects/Bio-Medical-Waste/Guidelines_healthcare_June_2018.pdf ).

Based on the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) data, every hospital bed in India generates roughly 0.25 kilograms of BMW daily. Studies indicate that the quantum of BMW generated in India is much lower than in other countries, including developing countries. However, this is only solid waste. Hospitals also generate significant liquid BMWs too. Details of the liquid BMW that HCF generate is largely unavailable.

Management of Bio-Medical Waste

Although BMW is a small proportion of the waste that an HCF generates, poor or improper segregation and management could contaminate other wastes leading to public health challenges. To ensure proper segregation and management, the BMW Rules 2016 classified waste into four categories and color-coded them. The yellow category includes all infectious waste, including anatomical waste, chemicals, and linens. The red category is the contaminated waste, some of which can be recycled, such as bottles. The white waste includes sharps, such as needles and metals. The blue waste includes glassware and vials, which can be recycled after treatment. The general waste is often binned in green bags.

Color coding is one of the simplest and most effective ways to deal with BMW. It helps to segregate the waste at the source by its type, thus potentially staving off any outbreak of diseases or infection. It also helps the waste treatment facility process the waste by its color. The segregation also helps to recycle part of the waste after treatment.

While the HCFs generate and segregate the waste at the source, using the specific colors in bins, the Common Bio-Medical Waste Treatment and Disposal Facility (CBWTF) treats the waste. Before 2016, the HCFs had to use their captive treatment facility. Currently, for HCFs in a radius of 75 kilometers, the CBWTF is responsible for collecting and treating waste. HCFs are allowed their captive treatment facility only if there is no CBWTF in the range of 75 kilometers. The CBWTF, established privately, is supervised by the State Pollution Control Boards (SPCB). The HCFs also apply to the SPCB for authorization to dispose of the waste through CBWTF or their captive treatment facility if there is no CBWTF in the range of 75 kilometers.

The challenges of Bio-medical waste management

The BMW management, however, still faces some challenges. The note highlights a few of these.

Non-adherence to guidelines by a few states:

Based on the data for the year 2021, the year of the latest data available from the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), a few aspects emerge:

- It is nearly seven years since the introduction of the BMW rules. However, only in eleven states is the entire or nearly the entire BMW treated in CBMWTF.

- In some states, only a proportion of BMW is treated in CBMWTF. In Assam, Bihar, and Odisha, only about 25 percent of the waste is treated in CBMWTF. In Chattisgarh, it is less than 50 percent. In Karnataka, it is about 60 percent. There is some challenge with the data from Bihar. States like Assam, Bihar, Chattisgarh, and Odisha rely on captive treatment facilities. For instance, in 2021, in Odisha, nearly 75% of the HCFs treated BMW in their captive treatment facilities. In Assam and Chattisgarh, it was around 31 %. It would be helpful to examine why these states cannot shift to using CBMWTF, as topography or geographical size is perhaps not a challenge.

- In the North-Eastern states of Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura, and Sikkim, as well as in Lakshwadeep and Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the BMW is not treated in the CBMWTF. The reason could be due to the topography and/or the size of the geographical area, which could pose challenges in setting up CBMWTF.

Institutional Challenges:

- The segregation of BMW at many HCFs has to improve. In some of the public HCFs we visited in a state, improper segregation of BMW by health personnel, patients, and their relatives were observed. Studies have documented this in other HCFs, too, during Covid.

- Many healthcare workers who transfer the BMW to a storage point in the HCF are usually engaged on contract. The contractual staff is rarely trained, and the team has a significant turnover. The lack of training has implications for waste management, transportation, and storage until it is handed over to CBMWTF.

- While there are monitoring committees in HCFs with more than 30 beds, monitoring is often an additional responsibility for the members in most public health facilities. The meetings are sporadic and often focus on purchases.

- Monitoring both by the health system and the Pollution Control Board is often sporadic, as they struggle with human resource availability.

- Data is a challenge. There is virtually no data on the liquid waste that HCFs generate, treat, and dispose of. Most public HCFs do not upload Form IV, mandated under the rules. The CPCB provides the data by calendar year; the latest data available is for 2021.

To conclude, it would be helpful to examine whether there is a need for a different set of rules for the states with hilly terrain and other geographical challenges. However, for states that do not have such challenges, such as Bihar, Odisha, and others, the reasons why they cannot treat all their BMW in CBMWTF must be assessed. To ensure better management, in addition to ensuring that HCFs provide the data correctly and regularly, capacity development and monitoring have to improve for the effective management of BMW and to ensure that there are no public health challenges due to poor management.

- “any waste, which is generated during the diagnosis, treatment or immunization of human beings or animals or in research activities pertaining thereto or in the production or testing of biological or in health camps, including the categories mentioned in Schedule appended to these Rules.”

- Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB). Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change. Government of India. Annual Report on Biomedical Waste Management as per Biomedical Waste Management Rules, 2016. For the year 2019. The total BMW waste generated per day is 619 tons and there are 24,86,327 hospital beds according to the CPCB data.

- Goswami, Mrinlani, et. al. 2021. Challenges and actions to the environmental management of Bio-Medical Waste during COVID-19 pandemic in India. Heliyon. Vol. 7. Issue 3. March 2021. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844021004187#bib80

-

Basavaraj, T.J., Shashibhushan, B.L. & Sreedevi, A. To assess the knowledge, attitude and practices in biomedical waste management among health care workers in dedicated COVID hospital in Bangalore. Egypt J Intern Med 33, 37 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43162-021-00066-9

Author: S Ramanathan, Founder Director at Development Solutions